(Content warning: historical racism)

I’ve been thinking about whether to write this blog. Whether it’d just be to patch my own soul, or whether it could actually contribute something. While not denying the former, I do think that there’s something that can be learnt from it. Where we are now, the Western world needs to change. There’s a lot of anger, a lot of misunderastanding and a lot of mistrust. You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. And if the horse starts kicking, what are you going to do then? The problem, as it were, is that the horse may well think that the water is poisoned.

Whenever you’ve got a movement like #metoo or #blm you’ll find two main antagonising groups. Firstly, you’ve got those who are ideologically against (male chauvinists, neo-nazis, whatnot), and then you’ve got the people who don’t have a firm opinion but are alarmed because (as we say in Dutch) “what the farmer doesn’t know, he doesn’t eat.” There are a lot of people in that second group.

When you look at society as a whole, you’ll still see a lot of segregation. Sure, formally everyone is equal and has the same rights, but socially the communities where people of different backgrounds, and skin colours, are living together are a minority. In the cities you’ve got ‘white’ and ‘black’ neighbourhoods, and in the countryside you’ll still have villages where there are non-white families.

When I grew up, and I’m in my mid-40s now, we had a village school with about 50 children, of whom 3 were non-white. They were adopted from Bangladesh and Indonesia if I remember correctly, by what we’d consider people from the ‘better middle class’. Aside from that, it was not until the Millennium, and the coming of an Asylum Seekers Centre, that the village saw a significant amount of non-white (and non-northern Dutch for that matter) faces…

Only a few welcomed them with open arms, while the majority started locking their bikes and back doors. “After all, you don’t know what kind of people you’ll get.” For the few years that the centre was near the village, the refugees were kept at arm’s length. Of course, the village’s actual waywards were indulged, and accommodated – as ‘missing stairs’ they may have been skipped over for generations, at least they were familiar missing stairs.

We had black people on television of course. The Cosby Show was unmissable, with the wholesome Huxtable family, minus daughter daughter Denise when actress Lisa Bonet became too scandalous. The A-Team came with Mr. T’s B.A. Baracus, who was the mercenary team’s strongman and occasional comic relief. Miami Vice had Rico Tubbs, conceived as “nobody’s Tonto”, though according to showrunner Michael Mann “that eroded a little bit.” I certainly don’t have any strong recollectons, other than pastel jackets with the sleeves bunched up.

The comedy series about a GP practice Zeg n’s Aaa (Say Aah) became water cooler talk in 1988 when a black GP and the white surgeon’s (white) niece got involved. Actor Kenneth Herdigein was born in Suriname in 1959 and came to the Netherlands in the early ’70s. As a young actor he refused to play criminals or drug addicts, and wanted to be an example for the young men in De Bijlmer, the ‘projects’ of Amsterdam: “In Suriname I was an outsider because I was too light, but when I came to the Netherlands I was too dark.” Those boys in De Bijlmer were far away from me and my brothers in Ulrum, though.

Our library had a few boxes with records, but no rap or hiphop. What music there was for the youth was pretty much decided on by the vocal majority, which basically came down to Metal and Madonna. Her “Like a virgin, touched for the very first time,” got a pass, of course. I don’t know what we thought where she was touched – her heart? What we did know was that Prince was a little pervert. Michael Jackson was fine, as long as he still had some of his boyish charm.

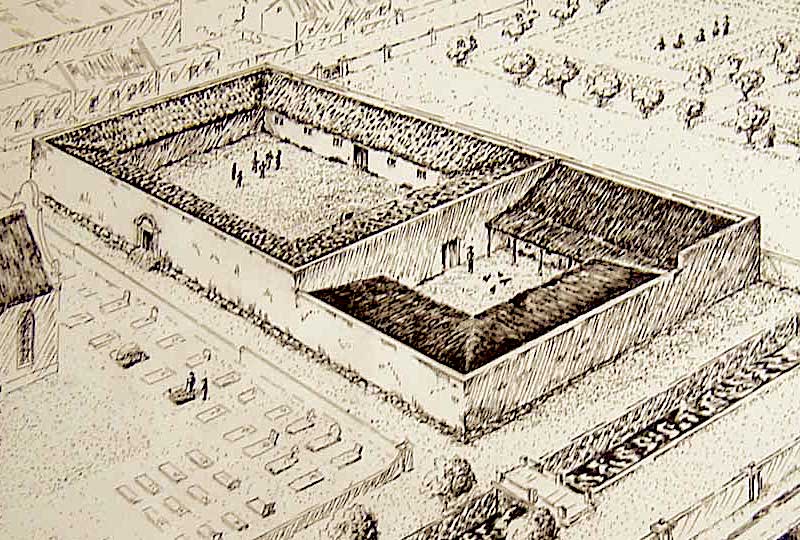

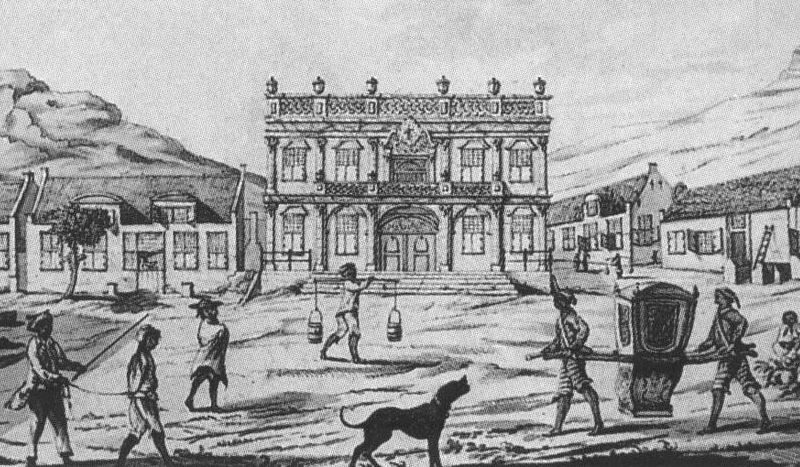

Ah, and the library had books, of course, through which a young boy from the desolate coast got to know the world. Like the books he has at home, his own and the hand-me-downs from brothers and parents, it’s a collection of new books, old books, and new books with old stories. These would of course include such standbys as Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Robinson Crusoe, a thankful ‘Man Friday’ rescued from savages, but also original Dutch fare. And there were black people in the Dutch books. Strangely enough, not from former colony Suriname but from Africa. Nor were there any people from our other ‘big’ colony Indonesia, come to think of. Perhaps another bit from our past we’d rather was kept buried.

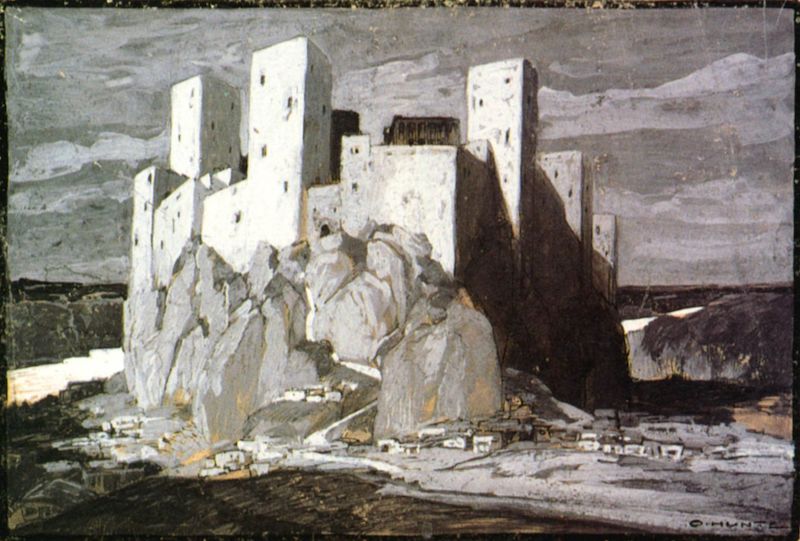

One of the comics I borrowed time and time again from the library is a facsimile reprint of an early book from the Suske en Wiske series, De vliegende Aap (The Flying Ape). It’s set in Africa and formed my image of Africa for years to come. They’re crude caricatures who speak broken Dutch and come with a giant cooking pot to stew Europeans in. Our heroes don’t mince words: “That n* even starts to swing! He’s more civilised than I thought!” In the 1968 this comic was redrawn, but the crude stereotyping, with lips filling half the face, and the racist slurs remained. Only in the last decade or so was the text adjusted.

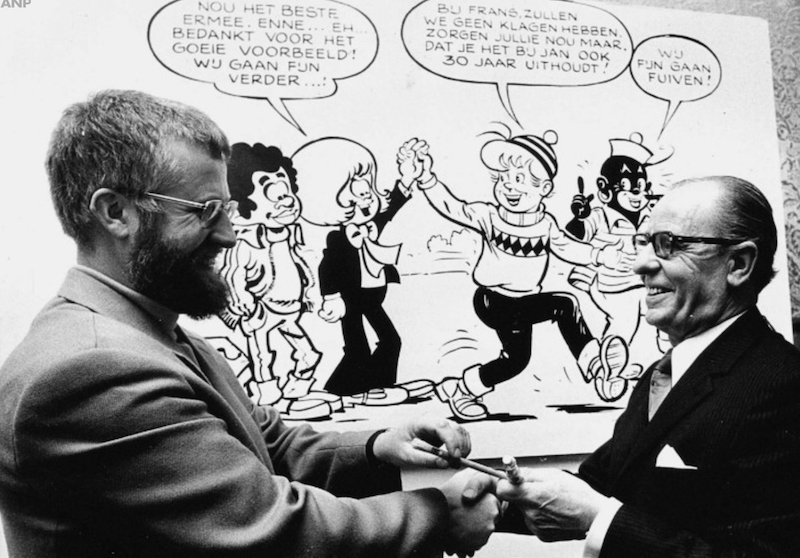

For decades a staple of Dutch comics Sjors & Sjimmie, about a white and a black boy. The white boy Sjors was ‘borrowed’ from an English comic in the 1930s; once adventuring in Africa he met the black boy Sjimmie. Sjimmie, drawn ‘as usual’ was not too clever, easily frightened and definitely the sidekick of bread-and-cheese grown Sjors. In 1969 the comic radically changed: “It was in the spirit of the times. I have taken the wildman Sjimmie and made him into a normal Surinam boy, like you’d meet on the street,” artist Jan Kruis said.

Bizarre: in the 1950s there had already been a restyling of the white boy, whose sailor’s uniform was seen as old-fashioned. In the middle of an adventure, the boy got a letter from his parents, calling him home. “Sjimmie very sad is. He now alone. What is Sjimmie without Sjors?” his friend frets. “Cheer up, Sjimmie, you’re not staying behind alone,” comes the reply, “you’ve got a new friend, the boy nextdoor. His name is Sjors too. Will you help me pack my suitcases?” It seems black friends are disposable, and transferrable. And a few panels later, Sjimmie seems happy enough alongside new-Sjors.

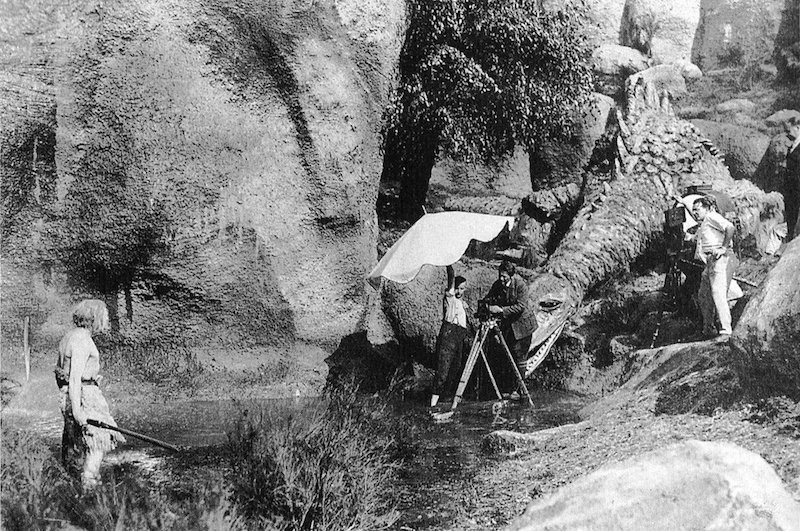

Another ‘fun fact’: Dutch filmmaker Henk van der Linden produced several films around the duo. Filming in the rural south, he often had difficulties finding a black boy, and several times a girl in blackface had to do, including his daughter: “Sjimmie was a fun type to play. I had to talk weirdly. That was in the script. My father had to stick to that. Nobody found it discriminatory at the time. Sjimmie was just a fun fellow, and whether he was black or white, we didn’t care about.”

Going through the children’s books and comics I read as a child is an onslaught of the same stereotype. People over a certain age, say 40, grew up with a huge amount of racism that was soaked into culture. This is true for The Netherlands, and I doubt it’s been much different for the UK or the US, and not everyone has had the opportunity, the impetus, or the will to address that.

I’ve been living in the UK for 15 years now, and working in an office where we regularly have young people starting who are fresh from The Netherlands. It’s almost a ritual that the first year they’re here, they get ‘the talk’: “Black Pete might be youth sentiment for you, it’s also a racist caricature.” A year later, they’ll likely give the talk themselves; it really is a lot worse when you look at it from the outside.

When I was 18, I moved away from the small village; first to the city of Zwolle, then to Amsterdam, where I lived for 8 years in De Bijlmer. Yes, ‘the projects’. During that time, I got ‘deprogrammed’ fairly well, but I’m thinking of all those people of my age who never left their villages, never left the white neighbourhoods, and genuinely can not see Black Pete as anything other than harmless fun for children. Cannot, or will not, as the price they’ll pay is too high, while they’ll get nothing back for it: why would they change their values for people they don’t know?

There does seem to be a disconnect between the ‘real’ black people we grew up with on television and those in our children’s books, but I think it reinforced something that I now see coming to the fore in the USA too. The black people in television shows and music, I think, were accepted as long as they conformed and didn’t rock the boat. This because from our books we had an idea of what black people really were underneath: impressionable, irresponsible and child-like at best, savages at worst.

And that’s what I think is what someone from the outlands, who doesn’t know black people, sees in the BLM protests. The question is not just how we give them a wider, more informed perspective: it’s how we make them want to see.

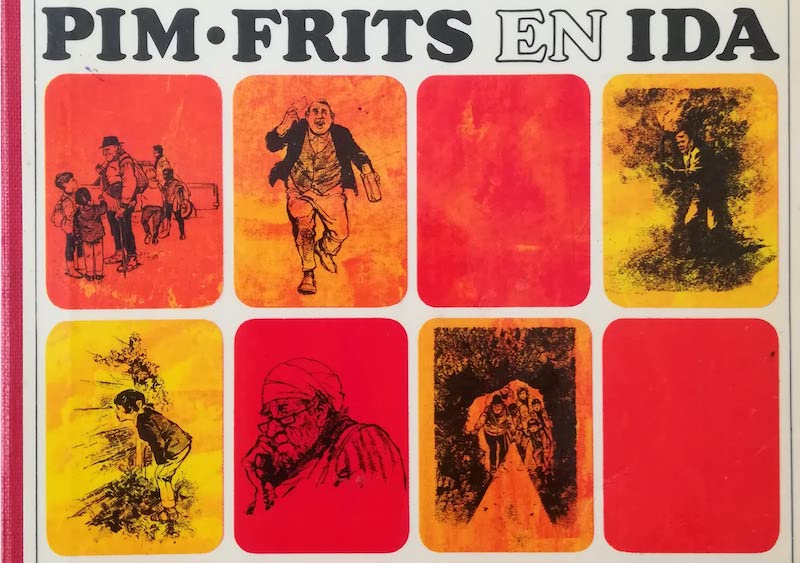

I’ve been thinking – were there no non-stereotype, neutral depictions of black people in the books I read a child? Yes, there was one book in the Pim, Frits en Ida series, which were read in school classes. I’ve looked it up; it’s part 8. I remember there’s a black boy temporarily in our heroes’ class, whose father is an ambassador. They set off on a school trip to the caves, and the four children get lost. They pretty much spend the rest of the book in pitch blackness…

(RvS)