Rudolf de Mepsche and the northern Dutch sodomy persecutions of 1731

“This inhuman tyrant found the wages of his cruelty in the following horrible death. The vermin devoured him alive – his appearance became so horrible, his lodgings so disgusting, that his next of kin could neither with money nor good words find anyone to help him in his last days.”

In his history of the province of Groningen, Dr. A. Smith positively gloats when he relates the fate of that scourge of the Groninger West Quarter, Rudolf de Mepsche, called the Devil of Faan. De Mepsche’s legend is not unlike that of Matthew Hopkins, though witch hunts were long a thing of the past for the God-fearing Dutch in the unquiet years of 1730 and 1731. It was the biblical sin of Sodomy that stirred them, sparked by a climate of religious strife and political instability. In the west of the newly formed republic the sodomite fever burnt itself out within months, but it came to a renewed crescendo in the obscure village of Faan, in the Dutch province of Groningen.

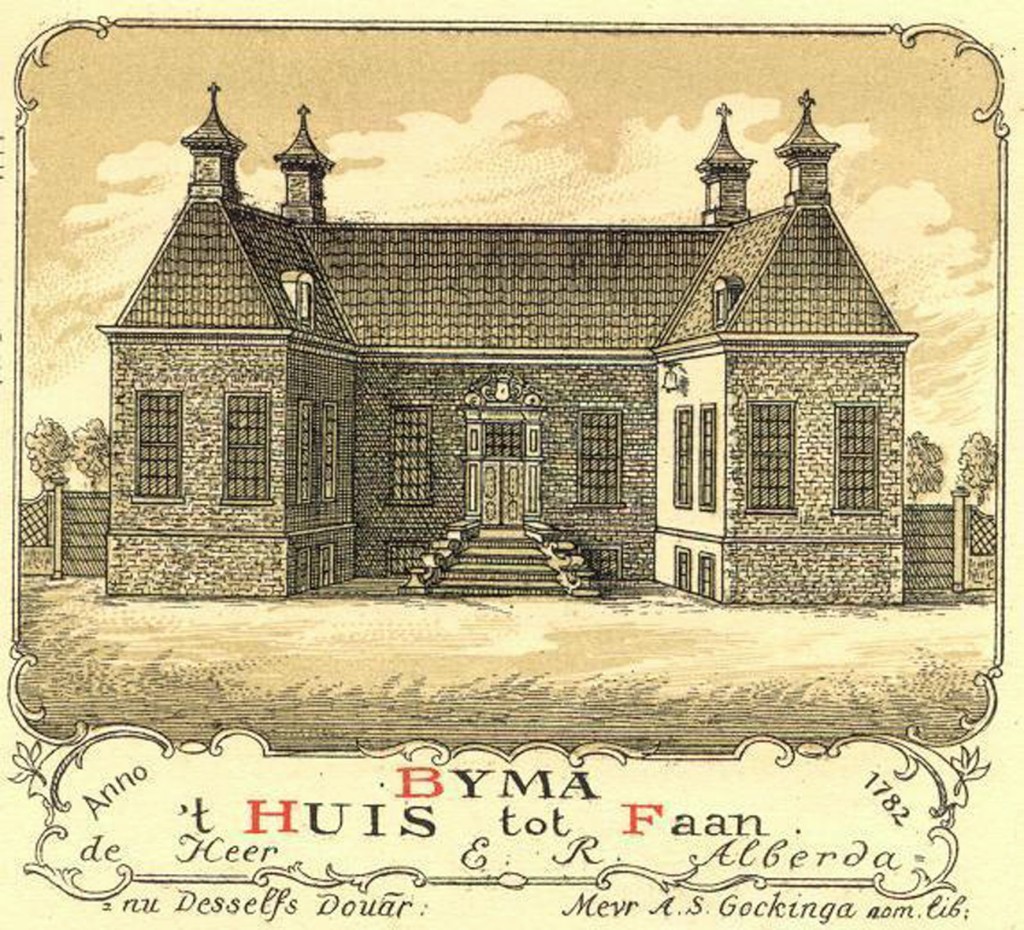

The landscape of the north seems desolate at first glance, but it has its own quiet beauty. Fields are marked by small roads and paths and clumps of trees. The land is flat, and when turning in a circle you can see the farms, villages and church towers to the far horizon. And there are many towers, because Dutch history is marked by religious schisms. Of De Mepsche’s borg, a stronghold turned mansion, nothing remains: it was demolished in the 19th century, its grounds cleared in the 1950s. All that remains is the driveway, now leading to the farm “Bijma”. It is as if the local powers wanted to erase all memory of the monster, and even recently plans to erect a monument for his victims were torpedoed. A plaque, the authorities decided, would suffice.

Almost unlimited power in an isolated community allowed De Mepsche to develop into a regional equivalent to England’s Witchfinder General. The supernatural shadow of his reign of terror extends well into modern times, and offers a prime example of how traumatic events keep local tongues wagging, and how the resulting folktales become accepted history. Credible books have been written about the terrible events of Faan, but ordinary people of the region will at best steer by a 1925 booklet by H.F. Poort, republished in 1986, exposing a whole new generation to its many errors and half-truths. The story roughly goes like this:

De Mepsche, or Mepske van Faan, was a corrupt and cruel nobleman who wanted to eliminate his enemies and seize their wealth. According to Poort, he finds “an article that speaks of Sodomia, an evil that especially in medieval times was punished with horrible torture and even death. With a grin he says, no, shouts out: That shall be it! That shall be it!” He tortures and hangs two dozen innocents, but for this terrible deed he is banished and finally dies horribly himself. The story doesn’t quite end there, though, and the farm on De Mepsche’s former lands is reputedly the focus of much supernatural activity. His ghost haunts there, they say, and each year on the anniversary of his death he tears at the blinds and howls from amongst the old beech trees.

A widely known story was told to Martha van Straten, mother of one of your authors, when she grew up in the village of Niekerk, not far from Faan. On the morning of the annual fair and cattle market of nearby Roden, farmers would find their cows loose in the stables. The following evening, she told us, the sky above Faan is blood red, with columns of fire and rising clouds of smoke: a reminder to the good farmers of the area of the horrors that happened in their midst. She is quick to point out that she never believed the stories, and when another local asked the residents of the farm about the wood panel from which the bloodstains supposedly could not be washed, he was told: “Och son, don’t let yourself be taken in.”

It has proven difficult to make sense of what really happened in Faan in 1731. Many documents became lost or were destroyed, ironically, for their immorality. It appears that Rudolf de Mepsche was a fairly unremarkable but diligent man. Born into an influential family in 1695, he was soon granted responsibilities in local administration, and while only in his mid-twenties he became Grietman of the district, a position he held until his bankruptcy in 1747. The whole province of Groningen consisted of the City and the Lands. The Lands were further divided in sub-quarters, each headed by a Grietman. De Mepsche had virtually absolute powers as Grietman of Oosterdeel Langewold, serving as its prosecutor, clerk and judge.

Rooted in Germanic, pre-Christian custom, this was originally a democratic system, with a new Grietman chosen annually from amongst eligible farmers. By De Mepsche’s time however, most farmers had sold their vote to either De Mepsche or his rival, Maurits Clant van Hanckema. The only brake on De Mepsche’s legal might was that all expenses for a prosecution came out of his pocket if the accused was cleared or unable to bear the costs of their trial and imprisonment. The law also tried to prevent corruption by not allowing a Grietman to preside over any case in which he himself had a stake or grudge. But these clauses offered little protection to a population that prescribed forgers to be burnt in a kettle, a churchbreaker to have his limbs broken and his head chopped off, and a traitor to have his heart removed – and then shown to him.

The penalty for the 22 men and boys De Mepsche convicted of sodomy was strangulation, after which the bodies were burnt. This in itself was not particularly aberrant for the times, but the speed and number of De Mepsche’s convictions was, especially for a small community consisting of a handful of villages. On Sunday 20 April a blind boy was the first to be questioned, on the basis of an anonymous note. On 24 September of that same year 19 men were executed and two young boys imprisoned for life. All but a few of them were poor, and the cost of trying them fell entirely to De Mepsche. He didn’t shrink from sentencing a personal friend to the harshest punishment of all: this man was burnt in the face with a torch before being strangled. So it can be safely ruled out that De Mepsche acted out of greed, or sought to eliminate his enemies – at least in the beginning.

It was only from the 18th prosecution that things got out of hand. He brought in the city of Groningen’s torturer, with well-off supporters of his rival Clant in the stocks. Clant complained about spurious indictments and the length of the “examinations”, but the city’s council consistently found De Mepsche to be acting within the law, and besides were loathe to meddle in what they regarded as a local affair. It is doubtful whether De Mepsche or his victims were quite sure what sodomy actually was. As all records prudishly speak in euphemisms – “sins against nature” and pecatum mutum de sodomiticum abound – we’re still none the wiser as to the state of their knowledge. Whatever it was, interrogations evoked tearful confessions and embarrassed questions about whether they could escape God’s wrath.

De Mepsche was on a moral crusade, albeit one horrifying by modern standards. But the instigator of the persecutions in the West Quarter is never mentioned in the legends and in Poort’s book he’s a mere accomplice, reluctant at that. Reverend H.C. van Bijler was an old student friend of De Mepsche, who appointed him minister of the churches of Faan and nearby Niekerk. He was a scholar and something of a writer, and to the isolated locals he represented a window on the rest of the world. Following the 80-year war with Spain (1568-1648), the newly formed Dutch republic was in a state of crisis, with merchant regents and the emerging Orangists vying for supremacy. Closer to home, recent decades had brought cattle plague and the devastating Christmas flood of 1717.

Van Bijler was sure that his country was about to go under, like Sodom and Gohmorrah, and when a pamphlet brought him news of the sodomy trials in the West of Holland, he knew what he had to do. Soon, he’d completed a book: Helsche boosheit of grouwelyke zonde van sodomie. It starts with a prayer but soon the reverend’s finger jabs: “…to the people who turn around the whole order of Nature, and have unfortunately imported the sins of terrible Sodom into our country, or still practice it. To guard against it and to punish it – the law of the Great God demands.” As a devout Christian, Rudolf De Mepsche could not have received a clearer call to arms to rout out the evil that undermined his own community.

After the first round of executions a few men still awaited trial. More arrests were made, now on increasingly shaky grounds, the last handful incriminated by youths who had been easily coerced. De Mepsche’s crusading spirits began to slacken as complaints piled up, with relatives and accused going over his head to petition the High Justice in Groningen. As a duly appointed oversight committee took its time looking into the matter, the costs of trial, the execution (including a platform, 3 ships with peat and 70 tons of tar) and now lengthening imprisonments began to exhaust De Mepsche’s coffers. In December 1739 the committee concluded that, as judge of the area, De Mepsche himself was the best person to decide if his own prosecutions were legal. Only in 1747, more than 15 years after their imprisonment, were the last men released who had been prosecuted.

De Mepsche could afford to be magnanimous: William IV of Orange had bested regents and been appointed to Stadtholder. As loyal supporter, De Mepsche got his debts paid off and he was also rewarded with a new position far from Oosterdeel Langewold. Ironically, for the rest of his life he laboured to dismantle the near-feudal system that had been the making and breaking of him: in Faan he’d been out of his depth, and now knew it. He died, following a slow decline in health, at the age of 59. He was buried in the Martini Church in the centre of Groningen with the highest honors accorded to a nobleman: preceded by drummers and torch bearers, dignitaries carried his coffin, with family, friends and city council members following – a far cry from the man who died, according to one narrator, like some inverted Midas: “Everything he wanted to eat changed into lice, spiders, earwigs, worms. If others ate from it, it was fine. But as soon as he wanted to take something himself, it was all vermin again.”

The legends may offer a more morally satisfying ending, but the truth provides no such comfort. A handful of accused languished for 15 years in prison without even being put on trial, while public opinion largely remained with De Mepsche. Yes, he had feared enough for riots at the executions to order 300 peacekeeping troops, but most people must have had some trust that God’s justice was being done. Besides, going to see a public execution was considered a grand day out in those days. De Mepsche surely also benefited from the contrast between him and Lewe, tyrannical lord of neighbouring Aduard, who provoked serious riots when he demanded crippling taxes for dyke repairs following the 1717 flood. The real question, then, is how acceptance of De Mepsche as local ruler could take a 180 degree turn into the image of Mepske, duvel van ‘t Foan.

The key to this is another shift in Dutch politics. De Mepsche was a loyal supporter of the Orange party when they were the political underdog, trying to break the power of the ruling merchant elite, but at the end of the 18th century the Orange family had acquired near-royal status and the general population had become thoroughly disenchanted with them. Mob mentality ruled, and pages were rewritten or torn out of the history books wholesale. Everything tainted with Orange was suspect, and generations now unfamiliar with the context of the trials had no truck with one who woud hunt and kill innocent villagers. That man, people said, must have been Satan incarnate. And so he became a local Bluebeard, an avatar of superstition and hatred.

Folk memory is persistent, as is the desire that justice is done: if not by men, then by higher powers. About a decade before historian W.T. Vleer wrote his critical study of the sodomy trials, he gave a lecture to a local club. When he started debunking some of the myths and misconceptions around the case, one old man jumped up and protested: “Mister chairman, this man is lying. It’s horrible. We were always taught that De Mepsche got his comeuppance, and now this man is claiming that God didn’t punish him? All lies, which as a decent man I won’t believe!”

Who are we to argue?

Literature:

H. Hofman, “Jeugdherinneringen van een Oud-Niekerker”, Oudheidskamer ‘Aeldakerka’, 1987

H.F. Poort, “Rudolf de Mepsche, of: De Faansche Gruwelen 1731”, Drukkerij Hekkema Zuidhorn 1925, reprinted 1986

K. ter Veer, “Protestants Fundamentalisme in het Groningse Faan”, Uitgeverij Aspect, 2002

W.T. Vleer, “Sterf Sodomieten. Rudolf de Mepsche, de homofielenvervolging, het Faanse zedenproces en de massamoord te Zuidhorn”, self-published, 1972