That the Dutch gift-giver Sinterklaas, Saint Nicolas, has little do with the historical Bishop of Myra may be well known. Why we do have the figure, or the related Santa Claus, is difficult to explain – it’s a rich stew of adopting, adapting, repressing, and resurrecting of traditions. If only the story was as clear as it was to the people of a century or so ago. The 19th century saw great advances in the reconstructing of our oldest history, and with it an emerging interest in our pre-Christian past; in Germany, the Brothers Grimm were busy and in Friesland the antiquarians were mercilessly trolled with the Oera Linda book. Legends, traditions and celebrations were dissected and with a measure of factoids it was proven that Sinterklaas, too, was pagan. This is how a lecture from 1902, by Dr Koopmans van Boekeren, explained Sinterklaas. Is there truth in it? Sure, but it’s never such a straight line, and for each ‘match’ that he made with a Pagan Germanic god, there will also be characteristics of these gods that he’s conveniently skipping.

With the introduction of Christianity we have received Sinterklaas because the evangelists understood that the new teachings had to be made palatable, and that was why Christian celebrations were made to coincide with Heathen ones. In Germanic theology you can find the explanation of the customs surrounding the Sinterklaas feast. Wodan, god of the elements, of wind, sea and storm, was highly revered by the seafaring Germanics. Saint Nicolas was originally also the patron saint of sailors; what was easier than swapping one for the other?

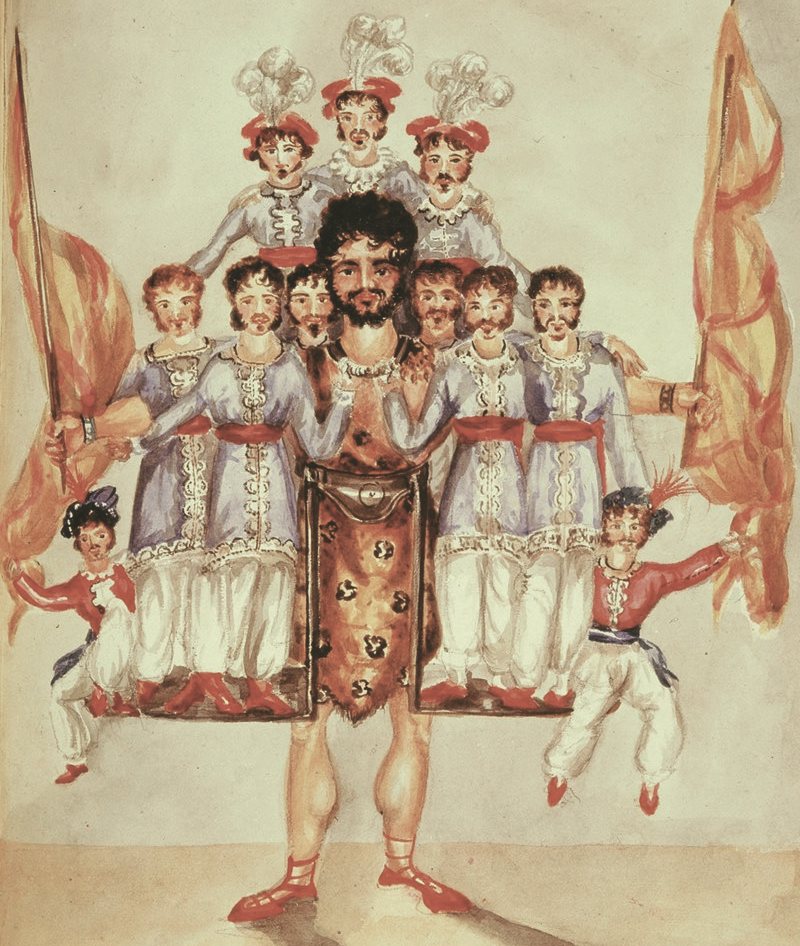

During the Jul Feast (25 Dec-6 Jan) Wodan rides his horse Slypnir, accompanied by the loyal Eckhard, through the sky and wears a wide cloak. There we have our Sinterklaas. Wodan is also the god of fertility, because wind creates fertility, and as such the time at which he is celebrated is the time of gift giving. Maybe there’s a bit of the god Janus in Sinterklaas. With the Sinterklaas pastry we are thinking of the Germanic Sacrificial cakes. Thinking of Fro, the god of light and protector of lovers, Sinterklaas became the “hylickmacker”, “wedding maker”. The “vrijer” and “vrijster” of speculatius is explained. Fro’s wagon was pulled by wild pigs with golden tufts, hence the Sinterklaas Pig. Pepernoten (ginger nuts), instead of regular nuts, remind us of Donar. The chimney is the connection between the ghostly world and the human in the Germanic theology. Putting your shoe in front of the fireplace is also Germanic. The bundle of rods is possibly the rod of life of the Germanics, with which they would beat against trees to make them bear fruit. Salt is the sign of wisdom. The helper is the loyal Eckhardt; probably there’s thoughts of fairies, and he’s made black to denote the invisibility of fairies.

And why does he come from Spain? Old-Germanic folk belief has an important place for the commemoration of souls. A soul could for example leave the body in the evening, and return in the morning. When someone died, the soul left the body and if a child was born a soul would settle in it. When souls didn’t live in a body they lived in a land of light and sunshine, the Engelland. This glorious land was, when facts got muddled, transposed to Spain, known as a country of light and sun, rich with lovely flowers and fruits.

All attempts to banish Sinterklaas during the Reformation were doomed, as Sinterklaas is not a Catholic holy man, and the Sinterklaas feast not a Catholic celebration. The speaker ends by warning his audience never to replace the children’s feast of Sinterklaas with Christmas; the latter has a deep and holy meaning, but will never be a children’s feast in the sense of the first.

Decades later they’re still not done with the Pagan Past. Grimm and other folklorists are still quoted, and the (pseudo)mythology would get out of hand over the next decade; sources from the later ’30s and the ’40s are suspect because their primary function was propaganda. From a northern Dutch newspaper article from 1931:

A shoe is put underneath the chimney. Putting your shoe with someone meant, in earlier days, to beg something from someone. The Wild Hunter (Wodan) fills shoes and boots with gold. In one of his fairytales Grimm tells us that on order of the Wild Hunter, a farmer takes off his boots, which are then filled with the blood from a newly shot deer. When he comes home, the blood has turned into gold. In Mecklenburg the bride puts a piece of gold in each of her shoes before her wedding – she’ll never lack for money. A serpent’s tongue in each shoe will make one invulnerable, according to folk belief. Whoever, at night, pulls three strands of straw backwards from the roof and puts them in his shoe will not be barked at by the dog.

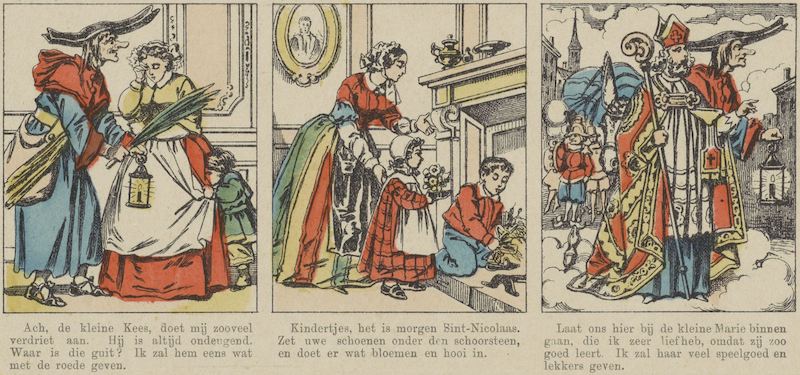

The shoe of Sint Nicolas is in the first place to put out fodder for the horse of Sinterklaas: grain, hay, straw, and bread will be put in the shoe in our province. Compare that with the many places in Germany and Scandinavia where a sheaf of corn is left on the land for Wodan’s horse. An offering for the God of fertility. And the shoe is chosen, as we could see, because a link with the magical world is found that way.

Black Pete carries a bundle of rods and a bell. The bell is for fertility. On Christmas Eve boys in a lot of German places walk round with belts full of cow bells; in the lower Inndal the youngsters cross in the spring through the fields with bells, “das Gras auslauten” to help the growing of grass.

Sinterklaas, Saint Martin, Ruprecht, all who give gifts are also armed with a bundle of rods. On 10th November, the Bayern shepherd gives his farmer, his boss, a green twig (Martinus Gerte) to stick behind the cribs or the stable door, to protect the cattle against disaster during the winter, and in the spring it’s used to drive the cows to the meadow. So, the twig also is connected with fertility, as with Saint Nicolas. In Switzerland Saint Nicolas has a decorated tree in his hand, in Hamburg a green branch.

But we spoil the twig, symbol of fertility, by turning it into an instrument of punishment.