Curious about the earliest mentions of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein in the Dutch press, I went for a search on the excellent online newspaper archive. Finding Frankenstein was not an easy task however, as Frankenstein is also a geographical location and there are dozens and dozens of mentions of a Squire Goll van Frankenstein, from Amsterdam, and his family. Oddly, the earliest mentions of the book are by way of Mary Shelley’s later works. In 1835, Mr. Freylink in Amsterdam offers an English edition of Lodore, and in 1842 the Estate F. Bohn in Haarlem has The Last Man for sale, in three parts.

In 1844 we get mentions of the German author Carl von Frankenstein, and of wounded soldiers transported to the hospital of Frankenstein (!), likely to be patched up and sent back to war. The liquor of one Polko from Frankenstein is being recommended in 1847, and then, something more tangible! The Journal de La Haye is an intellectual magazine from The Hague, in French. It mentions “monstre de Frankenstein” in relation to the “monstrous government which has suddenly arisen” in France, “like Frankenstein’s monster, to be the terror and curse of the waters that created it.”

Then! Finally! In De Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant of 19 January 1850, in the column “Sketches from London (from a Dutchman over there)” an overview is given of what Christmas is like for the Englishman, including an overview of the seasonal theatre offerings:

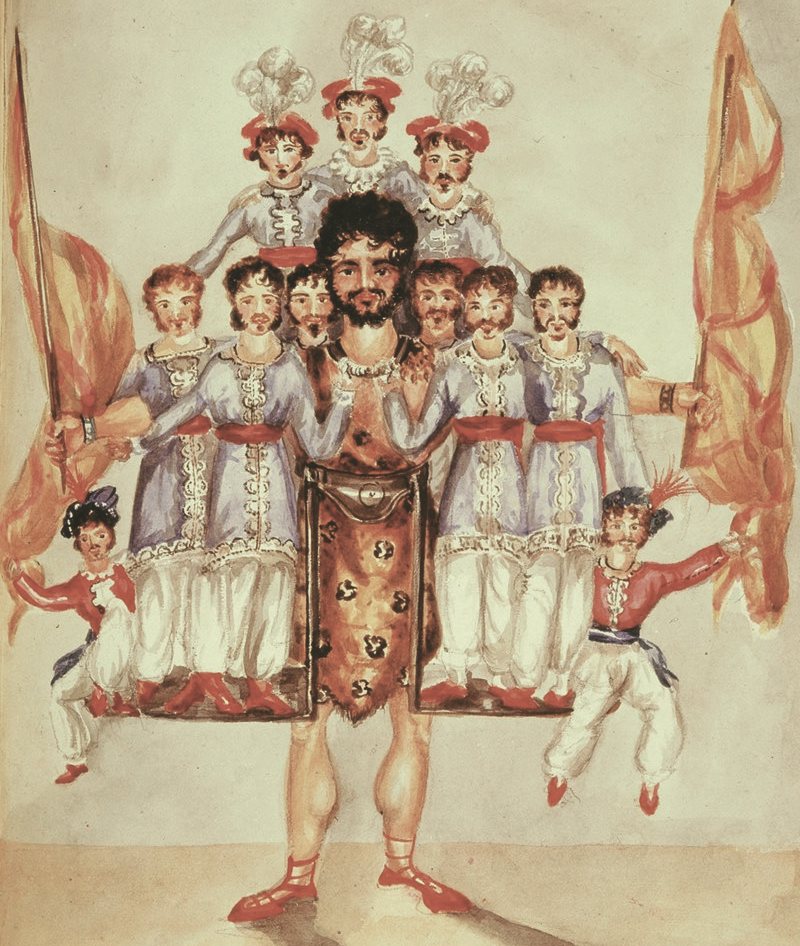

So were this year the pantomimes as follows: In the Durylane theatre: Harlequin and the good queen Elisabeth or the jolly England of the olden times; in the Princess-theatre, King Jacobus or Harlequin and the magic violin; in the Haymarket theatre, The ninth statue or the Jewels and the Genie; in the Adelphi Frankenstein or the Model Man; in the City of London, Pen, Ink and Paper; in the Queens, The sleeping beauty in the woods, or Harlequin with the golden horn and the magic goddesses of the silver water; (…)

1850 sees further offerings of Frankenstein’s English tooth powder, and the Java-bode, in November 1853, has a line in their serialised story: “Like Frankenstein, when his spectre visits him at his home, I did not know better than to flee from my bully.” Further, the newspaper Nederlands-Indië laments, in 1859: “We forget that there is a power that we ourselves have created, and which is stronger than ourselves, if we do not find a magic potion to control it. This Frankenstein of our own making is the press.” So, Frankenstein had become part of the collective subconscious – at least in the colonies. Was this because they’d read the original in English, was Frankenstein a book which was just not advertised in the newspapers – too sordid?

Alas, looking at the somewhat sparser magazine archive doesn’t give me much either – more advertisements for Lodore and The Last Man. “Dear Frankenstein!” starts an 1852 piece in Het Leeskabinet (The Reading Cabinet, a potpourri for cozy entertainment of refined circles – I kid you not!). However, it’s a travelogue of New York, and while I’m sure it’s of some interest, the writing of Hugo, Count of Böllinghausen and Nystadt did not entertain me. In an 1857 Wetenschappelijke Bladen (Scientific writings) Frankenstein’s creature pops up in a footnote, as one of the works of Percy Shelley’s wife, albeit as Frankenstein or the new Prometheus. Mary’s footnote is very quickly taken over by her father William Godwin, by the way.

Back to the newspapers then, because this is getting us nowhere! In 1861 the Society for Folk Crafts announces that it has improved sewing and stitching machines, from Frankenstein & Co, Dortmond. Close, but no cigar. The Baron Frankenstein that leads us into the 1870s is not the one I want either (he’s an envoy to Denmark), so I think it’s time to admit defeat. In pictures, the earliest are of Boris Karloff, in James Whale’s 1931 film, the one from Het Volk, daily for the Labour Party with a long and pithy review from which I’ll quote some bits:

The ‘Royal’ program of this week shows the film Frankenstein. There has been a lot of to-do about this film. It was at first razed to the ground in the American press, but despite this, or perhaps because of the bad reviews, it was a tremendous success at the box office. Then the film came to Europe. (…) The book was published in 1815, more than a century ago. It’s a work without lasting importance. The writer is Mary Godwin. We don’t remember her name from Frankenstein. Her father was a certain William Godwin, who wrote a sort of crime novel, Caleb William. The name of Mary Godwin has especially been remembered because she was married with the great English poet Shelley. In the prologue to this yellowed and forgotten book (etc. Seriously!) (…) Summarising this film with one word: f i l t h !