We talk about Sword & Sorcery a lot, but we know that not everyone who reads our work, or reads Fantasy in general, would think of themselves as S&S fans, or actually be sure where the line is drawn that separates it from other sub-genres. So, for starters, here’s some context on what it is, and was, and how you can draw a straight line from S&S to Game of Thrones.

If we had more marketing savvy, perhaps we’d have called what we write Grimdark and made the storytelling choices that go with it. That thought however is extremely depressing! There’s a reason Ymke doesn’t become the victim of the marauding bands of mercenaries in The Red Man: we’re straining towards a more hopeful (if imperfect) Fantasy world. We don’t resent Grimdark for existing (indeed, we’re avid, though not uncritical, fans of A Song of Ice and Fire and its TV incarnation in this house), but we can see how Grimdark has made modern S&S hard for the fantasy market to parse.

The assumption is that if you want that scratch that particular itch these days, you’ll either soak yourself into the nostalgia of the genre as it existed in the 1930s, or seek its distilled extreme in today’s Grimdark novels. However, neither of these perspectives really helps us deal with the ongoing presence and popularity of those pulp classics, Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories up front, and the editorial choices needed to ensure their survival in the genre’s future. To frame it in terms of a recurring S&S debate: do you prefer an edited edition or the pure text? Gary Romeo sums up the editing history of Robert E. Howard’s tales, and the crux of the issue, for The Dark Man Journal.

Part of the problem with the Conan stories is that fans often conflate L. Sprague de Camp’s unnecessary meddling and ‘posthumous collaborations’ in the 1960s with edits to remove racist references, and for a long time allowed a moral issue to be tangled with an aesthetic one – as Romeo’s post demonstrates, these were distinct decisions which De Camp himself explained: “I have, therefore made a few small adjustments to take the edge off Howard’s most cutting ethnic remarks. These changes have been very slight, since it would be ridiculous to try to turn Howard posthumously into a civil-rights activist.”

It’s progress that we can have a conversation about the racism in the work of Howard and his pulp era contemporaries without it being assumed that identifying racism means we want to junk an author’s entire canon – or indeed an entire decade, or genre, of fiction. This was also the age of Edgar Rice Burroughs and H.P. Lovecraft – indeed, Robert E. Howard and Lovecraft were friends, and Howard did call the latter out on his racism. However imperfectly, we can explore these issues and recognise that there is a choice to be made about whose work we focus on, how we understand its influence, and the implications of republishing it either intact or in edited form.

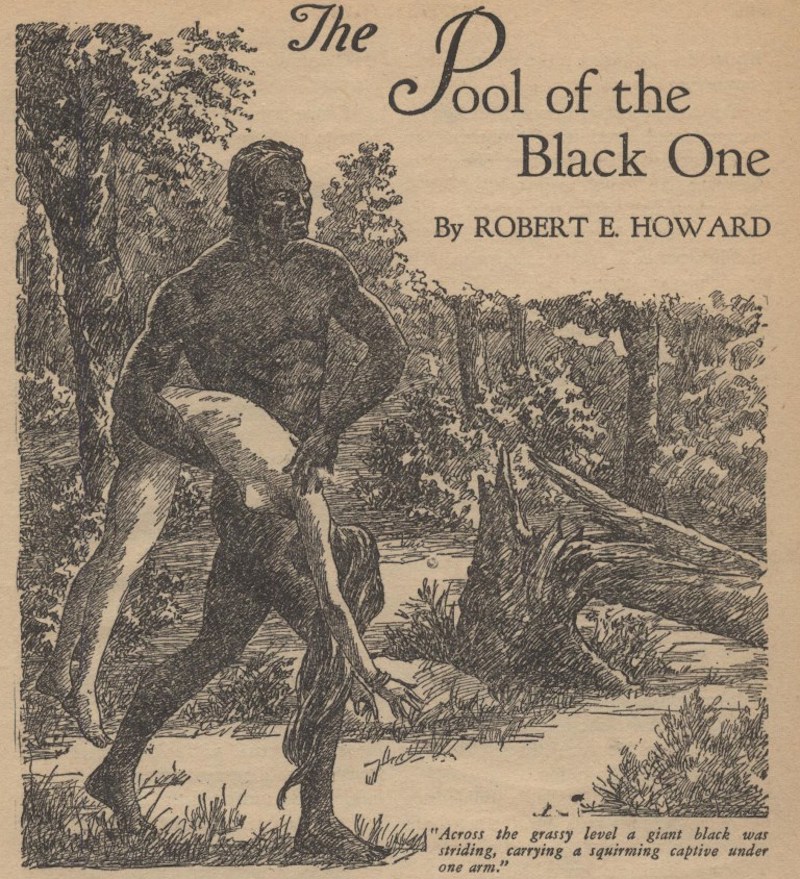

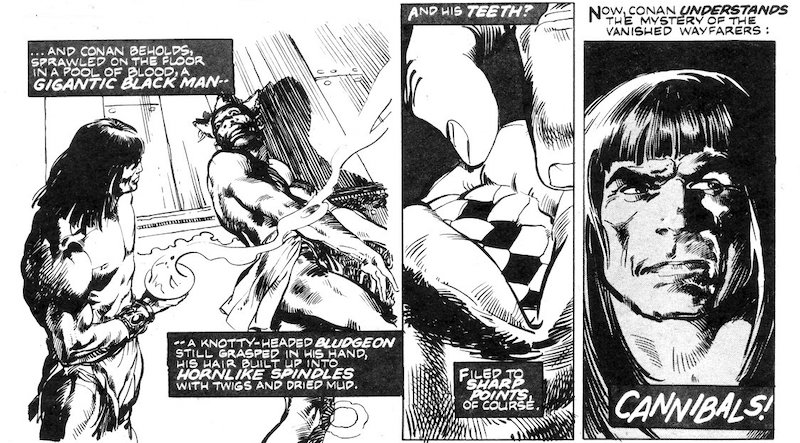

This is a complex and multifaceted issue, however. Removing specific slurs, as in the example from The Hour of the Dragon shared by Romeo, does not leave us with a totally racism-free depiction. Racism lies not merely in a single word that can be substituted for another, but in how stories portray an overall point of view. Nor is it a simple matter of hiding the racism of yesteryear from sight, and pretending it didn’t exist, or exert an influence on modern Fantasy. This however means it’s not simple, or even possible, to make classic Sword & Sorcery an entirely welcoming world for modern fans of colour (or female fans, for that matter).

While in Howard fandom many, including ourselves (above), will highlight the relative racism-awareness of Howard, as compared to Lovecraft, from a distance it looks reflexive, apologist. Yet it’s important to mention it, because it shows that racism was being debated in the crucible in which the genre was born, by the authors who gave us pulp in the first place. Racism is not the inevitable product of any one era, or something from which the progression of a society, or popular culture, is strictly linear. Yet so often, the people having the debate are white fans (again, including us) in an ageing corner of fandom. We know that’s not the whole story of either Sword & Sorcery or the wider fantasy genre, but that it even feels that way is itself part of the problem.

This all feeds into a perfect chicken-and-egg storm: for the casual browser, S&S will call images to mind of a mono-syllabic Arnold Schwarzenegger running around in his underwear, and its derivatives (speaking of which – Thongor?), and while a dedicated core of fans is desperately trying to drag the genre into the 21st century, there also is a very vocal group that likes it just fine without ‘wokery’, ‘snowflakes’ and ‘cultural marxism’. Exciting things are happening on TV (She-ra, Kevin Smith’s He-Man, Primal, The Troll and the Barbarian) which should drive a whole army of kids to Sword & Sorcery, I am sceptical. Let’s face it – S&S has a branding problem!

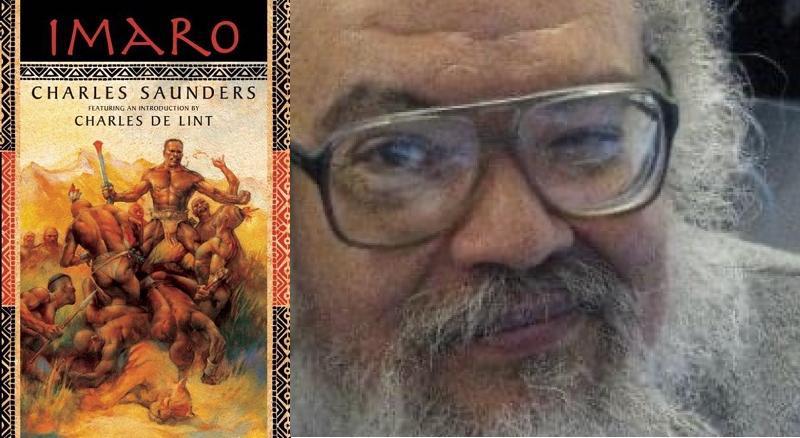

The fact that fans recently had to crowdfund a headstone for Charles R. Saunders, trailblazing Black creator of Imaro, and the founder of Sword & Soul, seems horribly symbolic of a fandom, publishing landscape and literary market that holds most tightly to its heroes after they’re dead, and struggles to even conceptualise Sword & Sorcery as a still-living genre. As Brian Murphy highlighted in an article for Black Gate last year, genres are malleable and often defined in hindsight. But, is it right that so much about defining Sword & Sorcery seems to rest on “Do we edit out the racism or not?” rather than on “How do we welcome in the fans for whom it’s a sticking point?”

It seems to us that there’s room for both the edited and unedited versions of the classics to exist, both to give readers the option of avoiding the most egregious language, and to acknowledge the fact that language existed at all. The Del Rey collector’s editions, being for a large part ‘back matter’, wouldn’t be the first choice of the casual reader, but there is indeed room for an “edited but not tampered with edition” that preserves Howard’s style without thrusting racist language upon the modern reader. Our concern is that the Weird Tales texts are in the public domain, and that this is what’s being casually reprinted, without context. We’re not convinced that publishers of a ‘popular edition’ necessary have a ‘thoughtful editing process’ at the forefront of their mind.

As we get older, we hopefully develop a more expansive frame of mind and become less likely to cry “outrage” or “cancel culture” at the prospect of editing. We don’t have children, but we’d not gift some of the books of our childhoods to friends’ kids. If entertainment, whether for young or old, is the primary goal of a particular edition of a book, then why insist on including content that hasn’t aged well, and compares a huge section of its potential audience, as in the original text of the Conan tale The Hour of the Dragon, to animals?

And without negating the value of original texts to readers who want to fully understand and study what was written and published during the pulp era, a ‘pure’ reading experience cannot possibly exist. The stories are not printed on pulp paper, between other bits of horror and under a Margaret Brundage cover, you didn’t buy your pulp magazine from the spinner rack at the drug store (or by subscription!), and you are not living in the 1930s. You bring your 21st century experiences, and – for most of us reading this – your post-WWII origins. You come from a world that Sword & Sorcery, in those few extraordinary years when Howard was writing, had yet to anticipate.

And if stories are racist (or sexist) in a way that can’t be saved by swapping out some words, then we can live with them fading away, and not being picked up by the popular press. This is not ‘Nazi book burning’ (despite what some Dr. Seuss etc. fans claim) – this is part of an inevitable process not limited to the pulps. Pick up a book catalogue from the 1930s and see how many titles remain in print now: very few. Things don’t fall out of print only because they’re bigoted or controversial, but because they become old-fashioned or irrelevant. For that matter, pick up a catalogue from 1990 and see what’s still in print. Should we complain about the 90% of books that aren’t, and scream that they’ve been ‘cancelled’ (and for far less reason than racism at that)?

So let us make a suggestion: every time the debate about whether eighty-year-old stories should be edited for racism arises, buy something by a modern sword and sorcery author. And specifically, lest this seem a sales pitch for our own work: let it be an author of colour. Check out Milton J. Davis, who wrote Meiji Books 1 and 2, three volumes of Changa’s Safari, and edited Griots: A Sword and Soul Anthology, which further showcases the diverse talent that’s part of the future of the genre. Read Balogun Ojetade’s Once Upon A Time in Afrika. Heck, have a look what the awesome people of FIYAH magazine have been up to!

Nostalgia has a lot to recommend it, but we also sometimes need to be able to lay nostalgia aside, so that it doesn’t obscure for us what there is to appreciate in the here and now.

I can certainly second picking up Milton Davis’ books, and it’s a good takeaway overall that as much as Sword & Sorcery fans tend to look backwards to the roots of the genre, it is still a living genre with present-day authors turning out solid material.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely – I’m a hugely nostalgic person, but in the end I get so much more out of knowing we’re not just curating the classics, but have new things to look forward to.

LikeLiked by 2 people